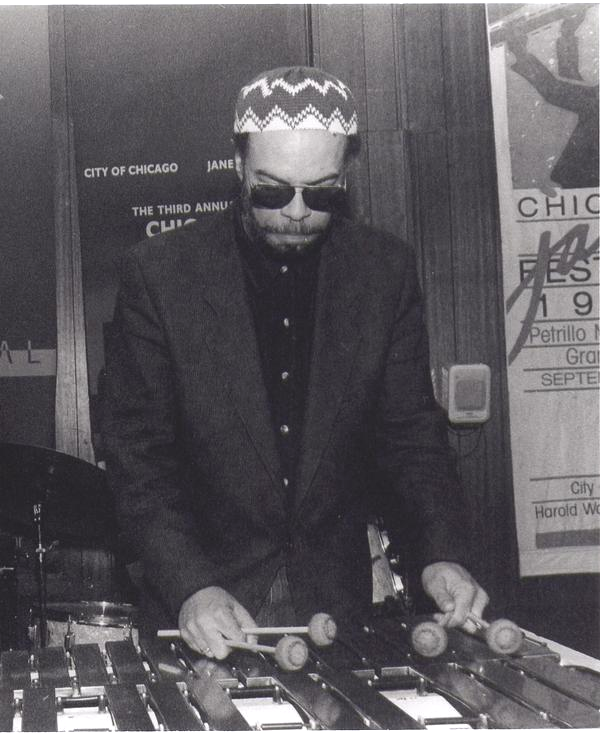

Our latest special feature is two short stories from Paris Smith. Paris is a Chicago fiction writer who has been published several times in Struggle. He has two collections of short stories and a novel in publication. Over the years he has been a newspaper editor, jazz musician, research project leader and an oil rig mechanic. He has played the vibraphone in jazz groups for many years. Included here is "Ghost of Yesterday," the story of the struggle of a musician, and "Hysteria," the story of a young Black boy in pre-civil-rights-movement South. Struggle readers will be familiar with "Hysteria," but I include it here because I fiercely believe that it is one of the finest short stories ever written in the United States. I nominated it for the Pushcart Prize but it was apparently ignored. -- Tim Hall

Ghost of Yesterday

Earl woke up suddenly, sweating and shaking, in a panic, thinking that a loud noise had erupted. He continued to lie still, listening again for the sound, whatever it was, but only the silence of his room prevailed.

He rolled over and stretched his arms while yawning. Lisa was standing at the window, peering out through the murky glass. At first he felt relieved at the sight of her, then he grew taut again, realizing he had panicked because she was no longer stretched out beside him.

He knew she was aware of his watching her, but she didn't turn away from the window. In profile, she appeared inaccessible and representative of the tensions raging inside him. Standing taller than most women, she exuded an air of nobility with a rather thin neck, and a head which she held up most of the time, even when the occasion called for drooping and despondency. She radiated freshness and vibrancy, the rosy hues of her skin defying enhancement from makeup.

"The rain let up," she said in her sultry, purring tone, turning finally to look at him. "It stopped for you, Earl. Just for you."

He laughed, but in his heart he felt she was being cruel. She knew that only bad luck or no luck at all came his way.

"What time is it?" he asked. "I've got to be at the Falcon Club tonight by nine."

She held her wrist a certain way while checking her watch, tilting her head a bit to the side and hiking her eyebrows, suggesting an aristocratic femininity.

"Eight o'clock. Are you going to eat before you go?"

He didn't know what to say. On one hand, he wanted to hurry up and get to the club, but on the other, he preferred to stay with Lisa for as long as he could.

Really, he wanted her to come and climb back into bed with him.

"What're you going to do, Earl?" she pressed. "Should I call and order something from the Chinese place?"

He marveled at her graceful moves as she went to pick up her cigarettes off the dresser. Her behind seemed to be rolling around underneath her short gown.

She was thin, but not what one could call skinny, and she had shapely legs.

"I should've got up at seven," he answered at last. "Lennie Trance doesn't go for that late shit. He's serious about his music."

Nodding, she picked up a lighter and flicked a flame. Closing her eyes, she pulled hard on the cigarette. For a moment she appeared much older than her thirty-one years as the smoke dissipated in front of her face and he saw where her jaw was a teeny bit crooked, jutting out a bit on the left, exposing an imperfection which made her look slightly mannish.

But in the next instant the ugliness was gone; yet, the same lines were there. And he wondered if he had really seen a flaw in his Lisa at all.

She smiled cheerlessly at him, as though she sensed what he was thinking about her.

"Guess I'd better get dressed and split," he said, tossing aside the covers and groaning when she turned away and didn't look at his naked body.

He stepped into the bathroom and closed the door. He tried not to look at his reflection in the mirror over the sink while he turned on the water, but his eyes couldn't stay off the aging face lurking in the glass. What did Lisa see in him? He appeared quite ordinary, with skin the color of cinnamon and a moustache some said made him look like Hitler. His hair was thinning in the top of his head and cut short and pressed into waves across the sides and back. There was a sloppiness in the way he stood, shoulders round, a tightness and hardness about him because he happened to be a poor man's son who had always lived one step ahead of the wolf.

He looked around the tiny bathroom. The fixtures were archaic and rusted, and there was a black spot in the tub from where leaky faucets had worn away the porcelain over the years. A pair of Lisa's panties hung on the towel rack. He held his nose close to them, and ran his finger around in the crotch and sniffed her lingering fishy-pissy fragrance.

She wasn't going to be with him much longer. He could sense it in the way she walked and talked, reading him sometimes with startling clarity, insinuating that his stature in the world of men didn't amount to much because he was living in a furnished room in the Fort Dearborn Hotel, on the outskirts of Downtown Chicago where the shadowy world of Skid Row blended into the muddled landscape inhabited by hustlers and transient show people, the chili pimps and shady businessmen.

He sloshed the water around in the face bowl and looked in the mirror at his pearly teeth. He could still flash the old charm. And that was how he first pulled Lisa. She had figured him to be a big-time jazz musician living the fast life. She had been looking for maturity and affluence in an older man, but she quickly found out the truth about him. Several times he had gotten drunk and wet his pants while they were out in public, and she had seen him guzzle down a brick of Wild Irish Rose around noon, then flop across the bed to snore and stink until four.

But she had also witnessed how the crowds cheered him on at night in the clubs when he blew his sax and seemingly frightened the other musicians with the sounds he made. And she had heard him blow his heart out especially for her one evening on the bandstand when he announced into the microphone that he was dedicating the band's performance of The Most Beautiful Girl In The World "…to a young lady, who's very dear to me, named Lisa." So she must've seen something real in him. His talent? His creativity? His energy? Or had he been fooling himself about her all along?

Snapping out of his reverie, he washed up and brushed his teeth, and spent the most time combing his hair and trimming his moustache.

"Who're you working with tonight at the Falcon Club?" Lisa asked when he finally emerged from the bathroom.

"I'm not sure. Lennie's got this guitar player coming in. A young boy out of Philly. And some dude named Smiley is playing drums."

She didn't watch him while he got dressed. Instead, she sat on the side of the bed, turning the pages of yesterday's newspaper, stopping now and then to scan something that caught her eye.

"You should come to the Falcon tonight," he said, knowing full well she had no intention of coming up to the Northside to hear him blow in the dingy little club. She preferred the ritzy Southside joints where the people dressed fly and the disc jockeys spun big-beat dance music.

The panic took hold of him again, and he hoped desperately that she would invite him back to the bed because he had the terrifying premonition that he was never going to see her again. But she wasn't about to cater to his wishes, and he couldn't beg. Not then. Not ever.

"I've some errands to run," she said. "But you be sure to blow something pretty for me, Earl. I'll hear you wherever I am."

Her words rang like notes of grim farewell causing his heart to sink. He put on his coat and sunglasses and paused to gaze in the mirror on the wall to the right of the door. Lisa came and stood beside him, holding his arm and leaning her head on his shoulder. She was toying with his mind. Didn't she know how much he was suffering because of her?

She refused to give him any more than a light kiss on the cheek before he grabbed up his horn case and headed out of the room, almost running, feeling like he had to hurry up and get away or he would never be able to leave her at all.

He walked to the end of the corridor and took the elevator down to the lobby where the elderly hotel residents sat around nodding, reading newspapers and staring off into space. The desk clerk, a white-haired old guy who was never without a toothpick in his mouth, glanced up from his paperwork and waved to Earl as he walked through.

A chilly blast of air greeted Earl as he stepped out into the night. The aroma of cooking food blew from the Chinese restaurant on the corner, making him reconsider his decision to put off a meal. The rain-soaked street appeared deserted except for the legless old man sitting in a wheelchair under the hotel canopy. A cup, holding a few coins, hung on the arm of the chair. He raised his head and smiled. The only tooth in his mouth protruded like a tartarous tusk from his bottom gum.

Earl stepped away into a faint mist that was starting to come down. He paused at the corner and looked inside the little Chinese place where he had met Lisa for the first time one night a month ago. A man wearing a black leather jacket was sitting at their table now. He glanced around nervously, as thought he felt Earl's eyes on his back. Earl moved on, leaning a bit to one side from the weight of his saxophone case.

He had wondered how he would take it when it was time for Lisa to leave him. After all, what business did he have with a woman so young? He could be in love with her, but how could she ever be in love with him? She had been destined to leave him from the moment she first arrived at his room. And now it was finally happening, and he was on his way to the gig - as usual - as though nothing out of the ordinary was going on.

Pausing again, he turned and glanced back at the hotel. Was she gathering up her things? Had she called a taxi yet? Was she going to be with a man more worthy of her? A sober man with real money and position?

He sighed and shook his head, realizing that he fantasized too much about Lisa. Not knowing what she was really about, he had prevailed upon her to stay with him, promising her a good time, and spending money on her he couldn't afford to spend. She was probably the kind of girl who was stepping and stomping her way through life, experimenting with good and bad and moving from one man to another; endowed with a lithe, graceful body and the face of a goddess. And most important of all, she had that snapping good stuff between her legs that made men pay to keep her. Earl had already exhausted the nest egg he had set aside in the bank.

"Can you spare some change?" spoke a gravelly voice.

Earl glanced down at a trampy-looking fellow with a hooknose covered with red eruptions. The man had walked holes through the cuffs of his pants, which hung low on his waist. Earl caught a whiff of something that smelled like poop.

"Can you spare fifty-cents," the man urged. "Give a little guy a break. I ain't had nothin to eat for two days."

Digging into his pocket, Earl came out with a paper dollar and handed it him.

Something unsettling stirred inside Earl as he continued on. Just two years ago, he, too, had been out begging for wine and food because he had no place to stay and was without a horn or a woman. Bleak times for a man who would never see fifty again. The musician's life had turned sour on him, and he had been cast out into the wilderness to roam the streets, drifting from bottle to bottle and flop to flop, sometimes having to sleep in abandoned cars or cardboard boxes beneath a Downtown bridge. During the bleakest moments he had stood on street corners looking up at the sky and feeling like a ghost; stripped of his past and lacking a future. Trapped in the here and now with himself. He had felt the grim reaper breathing down his neck many times; and he would have most certainly succumbed, had it not been for Jeff, the idealistic young social worker at the detox center, who happened to be a jazz fan and recognized him when the police brought him in after he was found passed out drunk one freezing night on West Roosevelt Road.

Jeff had salvaged his life for sure. He bought Earl a tenor saxophone from Mickey Feldstein's pawnshop on East Forty-seventh Street, and made sure that he was accepted as a resident in a Southside halfway house. Maintaining his sobriety for three months, Earl managed to get back in on the local music scene, and with a little more help from Jeff, rented the room in the Fort Dearborn Hotel and got hooked up with some food stamps.

Would he ever go back to those bleary days? Lisa evidently thought so. She figured he had never left them in the first place. The mark of the loser must've been emblazoned like a cattle brand in his face.

He hailed a taxi when the rain started to get heavy. The driver, an olive-complexioned Turk wearing a baseball cap, almost didn't stop for him until he ran out into the street waving his horn case and shouting, "Hey, give a musician a break, man!"

Earl hated to spend money on cab fare. He had just dropped seventy bucks on a new pair of shoes for Lisa; his weekly rent was due the next day, and the Falcon gig was paying barely enough to cover it. Mendoza, the beer-bellied hotel manager, didn't play around when it came to that money. If Earl came up late paying, his door would get plugged and his possessions held. He could've ducked in somewhere and waited for a bus, as he had originally intended, but he needed to get away quickly from the vicinity of the Fort Dearborn before he turned and went back to Lisa and made a fool of himself.

Traffic moved briskly through the Downtown district where just a few hours before, throngs of drones had clogged the streets, scurrying to and fro in the midst of the monolithic structures that were the symbols of steadfastness to the mechanized society, which worshiped them. Society was the herd. The multitude. The masses whom he had presumed for a long time functioned as a whole. But that had been before he realized how life carried on in streams, and that every man was traveling on his own course, bound only by his destiny.

It was during times like these, when the outside world appeared morbidly bleak and his thoughts tormented him with self-doubt and accusation, that he realized how much the music was helping him get through his life trip. Closing his eyes on the vapid panorama whizzing by outside the window, he began to hum a riff and pat his foot. The swirling sounds inside his mind's ear made him feel better. It was the beat. The one, two, three, four, one, two, three, four.

"Let me out in front of that liquor store," Earl said when the cab soon turned and started cruising along Rush Street. The rain had just about stopped.

He tipped the Turk a quarter over the three-dollar fare and received a sneer in return. A bleached blonde, prancing by in high heels and leading a white poodle on a leash, smiled at Earl as he climbed out of the taxi and headed into the store.

He bought a pint of Wild Irish Rose and ducked into an alley to drink half of it before he stashed the bottle inside his horn case. With the cloud of low spirits starting to lift, he walked toward the Falcon Club in the next block. The smells from the pizza parlor across the street made him feel hungry again.

The club was located in the basement below a novelty shop, which was closed for the day. He descended the short bank of stairs and entered a dimly lit room furnished with small round tables, and a bar, which ran the length of the wall. The stage was set up in the rear. A console piano and a set of trap drums took up most of the surface space.

The club was deserted except for a few couples sitting at tables and two men perched at the bar. Earl spotted Lennie Trance, the pianist and bandleader, huddling in the shadows beside the juke box with a robust woman dressed in black.

"What's happening, Earl?" called out Ziggy, the balding bartender, waving to him with his dishcloth.

Earl threw up his hand in acknowledgment as he headed toward the bandstand. He needed a beer right away to settle the pukey feeling in his stomach. He laid his horn case down on the stage and slipped off his coat.

Hermann Sledge, the lanky trumpet player in the band, stepped out of the men's room and came over to join him.

"Lennie's up to something," Hermann said in his deep, flat voice.

"What do you mean?" Earl asked, frowning at the dark-skinned man looming over him.

"I'm not sure. But when I asked him if were going to play Little Willie Leaps, he told me to forget all the regular stuff."

"What's he got in mind?"

Hermann shrugged and made a whistling noise through his teeth.

Earl opened his horn case and took out his neck strap.

Lennie Trance's boisterous laughter rang out in the club as he and the woman wearing black broke up their intimate conversation. She waddled over to the bar, her breasts and behind shaking like jelly inside her tight-fitting dress. The pianist drifted over to the bandstand and joined Earl and Hermann.

"What's up, Lennie?" Earl asked. "I hear you don't want to do the regular tunes."

"You got that right. I'm sick of that old shit. I got some new cats coming in tonight. Trying something different. Peoples' ears aren't primed for bebop like they used to be."

"Wasn't no rehearsal," Earl said.

"They already know the tunes. You and Herman'll hear them. Modal stuff."

Lennie's abruptness meant that his mind was made up about the music and there wasn't going to be any more discussion. He was a husky, bearded man, elegantly dressed in black velour slacks and a bright red sweater. Dark glasses shielded his eyes, and a diamond stud sparkled in his left earlobe. He exemplified self-confidence and jazz-life hipness.

Earl considered himself lucky to be working in the Rush Street club with the world-renowned pianist. Lennie had hired him to play the two-week engagement primarily because he owed Earl a favor from the old days when they were scuffling together in New York. Earl had introduced him to a very elusive, but influential, record company executive, and as a result, Lennie's career had blossomed with good-selling records and money-making engagements at festivals and night clubs.

Earl and Hermann headed over to the bar. Earl breathed a sigh of relief when the trumpeter paid for their beers.

"Your boss is quite the ladies' man," Ziggy, the bartender, said, popping his red suspenders against his white shirt. "He scores with a different chick damn near every night."

"Yeah. I wish I had that kind of luck in my love life," Hermann muttered. "I have to grip just to get one of these mooses to go out with me."

Earl winced when the thought of his young, pretty Lisa. Had she left him already? How could he face his claustrophobic hovel without her being there? Maybe she would surprise him and show up at the club to hear him play. God! He wanted her so bad.

He drank his beer and waited for his stomach to settle. He felt close to throwing up, and he knew he would never make it to the men's room, even if he started running.

"These must be the new guys coming in now," Ziggy said, pointing toward the doorway.

Earl and Hermann looked around as two men walked in carrying guitar cases. Both appeared to be no more than twenty-five years old; one fellow was stockily built, wearing tight, white pants and a blue blazer; his companion was a frowning, hawk-nose guy, with pomade-slick hair fashioned into a pony tail hanging to his shoulders.

"Jesus Christ," Earl intoned. "What the hell is Lennie up to? These dudes look like space cadets. They should be in one of those freak bands in that faggot joint up the street."

Earl's stomach finally settled down, but another part of him became upset as he and Hermann watched the new musicians bring in their amplifiers and plug in their guitars. Lennie Trance joked with them and gave some instructions on how they should set up on stage. Hermann walked away and disappeared for a while into a backroom.

The new drummer also turned out to be a much younger man. He arrived after the guitarists had their equipment in place. Wearing a stovepipe hat and puffing on a corncob pipe, he sat down at the drums and made a "swoosh" sound across the cymbals while showing his teeth in a sardonic grin.

Earl didn't say much when Lennie introduced the new musicians. The burly lead guitarist was named Rufus, and Fast Eddie Steel was the bass man. The drummer drowned out his own introduction with a sudden roll across the tom-toms.

"Trance has got to be crazy," Hermann whispered in Earl's ear when they were almost ready to open the first show. "These guys are rock and rollers. Strictly bubblegum."

"Lennie's the boss," Earl replied, shrugging and working the keys on his tenor sax. "He knows what he wants. I figure I'm just doing this little local gig with him, and hoping he'll take me along when he goes on tour."

There were no more than a dozen people in the audience when Lennie Trance sat down at the keyboard and sounded a thick chord, which blended out into a skittering of blue notes. Earl waited for some kind of cue from the leader, but Lennie never looked his way. Instead, the guitarist got the nod and started strumming an odd-sounding pattern while the drummer laid down a shuffling beat with his brushes.

After a few bars, Lennie raised his head and smiled before stomping off a faster tempo. The music then took off on a squalling, rollicking ride through what Earl perceived to be madness and cacophony.

Hearing specific melodic repetitions, Earl and Hermann stepped up to the microphone and blew some unison riffs which at first were drowned out. Lennie urged them to blow harder, but the guitar and bass, with their electronically induced powers, along with the pounding drums, dominated the proceedings. For a time, even the leader's piano became obscured.

Earl felt totally disgusted by the end of the first set. He put his horn down and stalked off the bandstand. The audience, which had increased in number, kept up its uproarious applause. Earl smiled at a chubby, middle-aged guy sitting at a rear table when he shouted, "I wanna hear Green Dolphin Street."

"What's happening?" Earl asked when Lennie came over and stood beside him at the end of the bar. "I don't know this music."

Lennie's brow became disturbed with furrows and his dark glasses reflected the neon light from the revolving "SCHLITZ" lamp hanging from the ceiling. Twisting his mouth into a snarl, he said, "Look, Earl. Things're changing. I'm putting together a new sound. I can't continue with the same old swing and bebop anymore. I'm tired of it. There's a demand for something fresh. My last two records didn't sell worth shit. The company won't renew my recording contract unless I come up with something to boost sales. That's the bottom line, my friend."

Earl felt a dropping sensation in his belly. He thought of Lisa, leaving him because he was old and from a passing generation. Now Lennie was telling him the same thing about the music.

"Get with it, Earl," Lennie said, slapping him encouragingly on the shoulder. "It's a new day in the music business. Time stands still for no man. Loosen up and blow with these cats. I'm gonna start using an electric keyboard myself."

Earl smiled and nodded, but he could feel the end for him with Lennie's band drawing near, just like he could feel Lisa leaving him. But being dropped by people was really nothing new to him. He had been cut loose by other women and fired from several jobs over the years. Perhaps he was perturbed more by it now because he was coasting downhill through his life and he dreaded being alone and idle - and old.

The rest of the evening turned out to be a hectic ordeal for Earl. He finished off the pint of pluck he had hidden in his horn case and ducked out during a break to buy another. He drank it alone, standing in a backalley doorway. He also downed several beers and a couple of shots of Jack Daniels at the bar. He was good and drunk by the time the third and final set rolled around.

"You guys don't know what this music is all about," he started preaching to the guitar man while they were taking their places on the bandstand. "Do you know about Charlie Parker and Lester Young? Do you know about Trane? Yeah, let me school you boys. I worked with Trane at the Peps Lounge on Broad Street in Philly, and I used to woodshed with Chet Baker."

The guitar player nodded politely then sneered when Earl coughed and looked away.

"It's all in the phrasing," the old sax man rambled on, staggering a bit and blowing spittle. "You dudes don't play with any phrasing. You just play loud. Have you heard of Charlie Christian? Now he was a great guitar player. The greatest."

The guitar man eased away from Earl and went over to whisper something in the bass player's ear, causing him to grin.

"Yeah, these young bucks don't know nothing about jazz," Earl grumbled on, more to himself now than to the others. He let his horn hang in front of his poked-out chest while he pulled up his pants. "I've blown with the greats," he bragged on, directing his attention back to the younger musicians. "I toured Europe with the Clarke-Boland big band. I played Jump Monk with Chazz Mingus in Fifty-five at the Bohemia."

Glancing around, his eyes opened wide and he almost cried out when he spotted a slender girl he thought at first was Lisa taking a seat at the bar. He quickly realized his mistake when she turned and spoke to the dapperly-dressed man who sat down beside her.

Earl started blowing ever so softly through Cherokee while the rest of the musicians took their places. With the bell of his horn turned away from the microphone, he breathed out the lowest notes, making a fuzzy rasp in the mouthpiece. For a moment he was back in the old days, in the company of guys like Bird and Prez, during a time when their music had reigned supreme. His chest swelled as he gazed out over the audience. The smoke was rising and disseminating above the crowd while this licks dipped and twirled in and out of the harmony that sounded inside his head. The music set a groove for the people. The songs were full of passion and blue notes. The sounds from the instruments came through reed and wood, through hide, and through brass and steel. Earl could stand there and slip into a nod and blow; so high that he would feel like he was having a sexual sensation.

But the raucous twang of the amplified guitar shocked him back into the present. Lennie was sitting at the piano and counted off the tempo for the first number. The rhythm started out heavy and became heavier, the chord changes remained static and resistant to Earl's pet clinchers and turnarounds. He tried to blow a solo on the tune, but his efforts spilled out in disconnected phrases, sparse and lackluster. He felt clumsy and agitated. No one seemed to be paying him any attention.

The next tune turned out to be even worse for him, and he let the guitar take over completely.

Lennie Trance seemed somewhat pleased at the end of the night, especially after the audience gave the musicians a tremendous round of applause and called for an encore. Earl, however, felt weakened as he packed away his horn. No one had said it, but he was sure he wouldn't be coming back with the band. It was the end of an affair, just as it was the end between him and Lisa. A dull ache started somewhere deep inside. He was losing the two things he loved most in the world.

"There's lots of fakers," Earl began, standing beside the bandstand, his clothing disheveled and a dribble spit about to drop off his chin. "Bullshitters and fakers. That's all who's coming up in this racket these days."

"Take it easy, Earl," Hermann said. "You want me to drop you off at your place?"

"Hell, naw. I'm nobody's baby. I was raised up on Thirty-ninth Street, in a tough neighborhood."

A look of concern crossed the trumpet player's face before he walked away. He paused at the front door and glanced back, but Earl paid him no mind. Hermann turned up his collar and left.

"These chumps don't even know what jazz is all about," Earl rumbled on, gesturing with a sweep of his arm toward the guitarist and bassist. "Just making a lot of noise. Musicians were a different breed when I was coming along. Me and Sonny Daniels had the slickest horn section in the business back in Fifty-eight."

Lennie Trance walked over to him and slipped a fifty-dollar bill into his palm. "Be seeing you around, Earl," he said with a heavy flavor of farewell reeking in his tone.

Earl stared into the pianist's guarded eyes, but didn't say a word. A dreadful chill came over him despite the volume of alcohol rushing through his veins.

Lennie walked away and joined the girl in black sitting at the end of the bar.

Earl grimaced as he picked up his saxophone case. For some reason, it felt extra heavy and seemed to be pulling him down as he trudged to the door with his head hung and a fullness in his chest.

A faint drizzle was falling when he stepped outside into the cool, night air. He stood in front of the club, watching the traffic and the passersby. Another girl who reminded him of Lisa hopped out of a taxi and scampered on a pair of pretty legs into the restaurant on the corner. He fought down the urge to follow her.

A couple of guys almost bumped into him as he staggered a bit and veered out across the sidewalk.

"Excuse us, Pops," one of the men said, squeezing Earl's elbow and steadying him a bit.

Before Earl could get a good look at the men, they had disappeared inside a doorway.

"What do you mean calling me Pops?" Earl ranted, shaking his fist at them. "I can still outblow any of you pootbutts. Yeah! Outblow, outdrink, outfight and outfuck!"

"Hey, Earl," someone said behind him. "What's the matter, man?"

He whirled around as the drummer and guitar man were emerging from the club.

"Somebody give me a square," Earl demanded.

"You got it, Earl," said Rufus, the guitar man, taking out a pack of cigarettes and tapping one loose for him.

"You guys want to take over the world with that crap you play," Earl chided. "Well, I'm here to tell you it won't work. You got to come through Bird and Trane, and all the rest who paid their dues and made this music great."

The drummer sneered and adjusted his stovepipe hat. Rufus slipped the cigarettes back into his pocket and shrugged.

"The people won't stand for your phony stuff," Earl went on. "They'll tune you out. I don't dig it, and they don't dig it."

"Seems to me the audience liked us fine tonight," Rufus retorted. "Lennie liked us, too. And by the way, he said you won't be back with the band anymore. He's calling in another sax player." Then Rufus' heretofore kindly-looking eyes took on a fiery and vengeful cast as he reached and tapped Earl sharply in the chest with his finger and said, "And you know what, Earl? Nobody cares what you dig and don't dig. You dig?"

There was a moment of silence between them wherein the night sounds of the city became very loud in Earl's ears. A siren wailed somewhere in the distance; a truck roared and coughed; a fit of laughter erupted. Then suddenly, the guitar player reached out and gave Earl a hard push, causing him to drop his case and stumble backwards until he made an awkward step and fell down in a puddle of dirty water next to the curb.

"I'm tired of hearing your silly mouth, old man," Rufus said, as he and the drummer stepped away. "You're lucky I don't kick your old, gray ass."

Earl looked up at the black sky and groaned. An outburst of snickering laughter was raised by someone behind him, but he didn't turn around to see who it was. Bracing himself on his trembling arm, his hand pressed into the curbside muck, he struggled to his feet and began brushing himself off. The seat of his pants was soaked through and his horn case was wet.

He slunk away to the corner and flagged a taxi, which took him home to the Fort Dearborn. The desk clerk eyed him curiously as he trudged across the lobby with the wet spot glaringly apparent on his pants. He felt like the lowest crawling thing in the filthiest place on Earth as he gazed at his reflection in the mirror next to the elevators. He didn't like the bedraggled old drunk he saw standing there with muddy streaks across his cheeks.

Groaning softly, he looked away. The seat of his pants felt soggy and clinging. A feeling of foreboding made him shiver. What would he find in his room? Would Lisa still be there? He dreaded finding out the worst.

The elevator came and he rode up to his floor. His feet felt like lead as he plodded down the hall to his room. Lingering at the door, he pressed an ear to the wood, hoping to hear the radio or maybe even Lisa's snoring wheeze. But there was only silence.

He slid his key in the lock and turned it until the tumblers clicked and the door swung open. The light from the hall swept across the neatly made bed as he stepped into the room. He let out a muffled whimper and dropped his horn case. Drawing a deep breath, his lips tightly pursed, he pushed the door shut and flopped down in the chair beside the dresser. All was silent, except for his breathing. He flicked on the little table lamp. He was alone again and on the verge of being broke. In a few more hours, Mendoza would be sitting in his office expecting the rent. Earl was a few dollars short. He would have to get out on the street and panhandle like crazy to make it up.

"Lisa, Lisa," he mumbled, as the pain came up in his chest, mingling with the self-pity and loathing already fermenting there. He felt overwhelmed by the malevolent feelings he harbored for himself. He felt like a foolish man. A man who had somehow fallen through the cracks in life, somewhere between the black keys and the white keys. His dedication to music had ultimately done nothing worthwhile for him. All those old gigs where he had played his heart out, walking the bar honking and blowing and bringing lovers together in the night, meant nothing now. They were just faded memories.

But had any of his musical life been real? He had never been able to read and play music with any professional skill. The best he could do was to follow simple lead sheets and improvise over chord changes. He had always worked through being a hustler. He had exaggerated to an extreme when he told the musicians at the club that he had toured with the Clarke-Boland band. He had got the chance to sit in one time and play a solo with them at a festival in Milan. He could've never played regularly with that kind of a reading band. And he had never really worked any gigs with Coltrane in Philly, or anywhere else. They had jammed together on some blues changes a couple of times at a local lounge, but that had been it. But Earl could blow on what he knew how to blow on. He could sound good and he could entertain.

He slid down out of the chair and started crawling toward the bathroom where he kept his razor in the medicine cabinet along with his sleeping pills. "God, I don't want to go through this shit anymore!" he cried aloud.

But he never made it to the bathroom; instead, he groped over to the window and got up and opened the blinds so that he could look out upon the sleeping city as the first glimmers of daylight were rising out of the man-made canyons of glass and stone.

He turned away and went and opened his case and took out the horn. With quivering hands, he attached the neck and mouthpiece. Returning to the window, he raised it high and drew in a deep breath. For an instant he contemplated hurling the golden horn out into the wind, so that it would land somewhere on the cement and shatter into a million pieces, but instead he went on and started playing. The first notes he blew sounded low and mournful. Then closing his eyes, he reared back and let all his tensions gush out into the horn to be transformed into a droning chant, high and low, raspy and mellow. His music flowed; his tears flowed. His song rode the winds and found its way into the nooks and crannies of the still sleeping city. He was calling upon the ghosts of yesterday to somehow come out of their hiding places and stand with him in the light. He couldn't handle this world by himself anymore. His forlorn refrain touched the ears of the sleepy-eyed men riding the garbage trucks, and the hungover waitress on her way to serve breakfast in the downstairs café. An old man, sleeping in a doorway off from the alley beside the hotel, turned over and looked up in the direction of the sound. Earl's melody became a collage of phrases strung together with bits and pieces from all the old songs he knew. The breeze came, blowing the stream of notes back at him, making him want to play on forever, to perhaps ride the winds himself and never again have to face the tiny room and the pain that waited for him on the other side of the door.

Did he hear voices and music in the wind? Were the ghosts answering his call for help? A drumming rhythm joined in, faint and far away. He paused and took the horn from his mouth. The thumping continued. Then he realized the sound was coming from behind him. Someone was knocking on the door.

"Who's there?" he called out in a strained voice.

There was a reply, but he couldn't make it out. Again the knocking came and an upsurge of panic caused him to groan. Had someone from Mendoza's office come to reprimand him about his sax playing? He had been warned once before, a couple of months ago, when he'd gotten drunk and felt like breaking loose and blowing his horn. He looked furtively out of the window as the knock came again.

Moving over to the door, he turned the knob and slowly pulled it open. Standing before him, clad in a pink house robe, was a dark-haired woman with a heart-shaped face and high cheekbones. She looked to be on the high side of forty with faint streaks of gray running through her hair. She was holding a can of beer in one hand a smoldering cigarette in the other.

"Hello," she said. "I couldn't help but hear you playing the saxophone. My name is Rose. I live above you on the next floor. All those old songs bring back so many memories."

"Sorry if I woke you up. I was just in a mood, you know."

"Oh, no, I'm not complaining. I couldn't sleep anyway. It's a blessing to hear you play your horn instead of listening to the mice running and squeaking behind the walls."

Earl's gaze fell upon her ample breasts heaving under the house robe. She was wearing pink slippers with little white tassels on the top. He couldn't see her legs, but he had hunch they were nice.

"You want to come in and sit a while?" he asked, smiling after a long pause while fingering the keys on his horn. "My name is Earl."

"I don't mind," she replied. "I got some more beer upstairs. I can go get it. Maybe you can play Body And Soul for me. That's my song."

"Sure, Rose. I can play it for you. It's one of my favorites, too."

He left the door ajar while she went to get the brew. He laid the horn down on the bed and let out a sigh. A gust of wind came through the window and blew a piece of paper off the dresser. A menu from the Chinese place. He picked it up. There was a phone number scribbled on the back. It was Lisa's sister's number. An upsurge of glee made him smile. Maybe he could call and get in touch with Lisa and persuade her to come back to him. He could beg and cry, and tell her how beautiful she was and how much he cared about her. He could make all kinds of wonderful promises.

But his joy quickly ebbed. He was just kidding himself. He knew she hadn't intentionally left the number for him.

Again the wind came and he thought he heard more of his music blowing back at him as he changed his pants and stepped into the bathroom to run a comb through his hair and check on his smile.

Soon, footsteps pattered in the hall, then the door hinges squeaked and Rose returned carrying a six-pack of beer. She was wearing red lipstick now, and dangling earrings shaped like crescents. The sweet smell of cologne titillated Earl's nostrils and prompted him to smile.

"Have a seat, sweetheart," he said, motioning to the bed as he ripped up Lisa's number and tossed the shreds of paper into the wastebasket.

Hysteria

"Wesley! Don't ya hear yo momma callin you, boy?"

Chester Sledge lumbered across the weed-choked front yard, favoring his left foot with a dip in his step, his bottom lip and paunchy belly sagging loosely.

"Ya better get a move on it. Ain't nobody got no time for no foolishness."

Wesley was careful not to let the screen door clap shut behind himself when he stepped out onto the porch. He yawned and gaped inquiringly at his daddy, his big brown eyes still swollen with sleep.

"Yo ma wants ya to take the washin back to Ma'am Kent. I heard her callin you bout half hour ago. And I want ya to stop at the store and pick up some salt on yo way back."

"I was comin, Daddy," Wesley mumbled, dropping his gaze and stuffing his hands into the pockets of his faded overalls.

"Gits so it's hard as hell for you to move in the mornins, boy. Maybe you need some good leatha on yo backside."

Wesley's lips quivered as a hot surge of unpleasantness shot through him, making his bladder tingle. He didn't want to displease his daddy. He dreaded one of those whippings where the old man would hold him up by his arms while he tore up his bottom with that heavy black strap.

"Don't keep standin there like a damned dummy, Wesley. Go on and see what all yo momma got for ya to do."

Wesley bolted down the stairs and dashed around to the rear of the old frame house where Holly Sledge was standing over the big cast-iron pot, stirring a batch of clothes with a long pole. The flames underneath lapped up around the bottom sides of the black bowl while a mixture of smoke from the coals and steam from the cleansing brew dissipated into the air.

"Where ya been, Wesley? I knows ya heard me callin ya." Frowning at him, his mother set the pole aside and wiped her face and hands on her apron. She was a frail woman with gangling arms and knobby elbows. Her reddish-brown hair, pinned back and slick with pomade, glistened under the morning sun. Her hands were callused and crusty. A deep, hook-like scar made a gash through her left eyebrow and tapered off across her nose.

"Git yo wagon and take them clothes there back to the Kents." She pointed to the bundles on the table by the back door. "Ma'am Paula's supposed to give ya a dollar-and-a-half. Ya hear?"

"Yes, Momma."

"Them Kents oughta be payin at least two dollars by now," his mother went on. "I know they got money cause old man Kent owns the town newspaper. They always got a bunch of clothes. And he's so damned particular bout the starch in his collars."

Wesley made no reply. She was fussing more to herself than to him. He shuffled over and pulled the wagon out from its space under the back porch. The axles squeaked and something rattled underneath. It was a vehicle he had put together using pieces of wood and the wobbly wheels off a discarded baby carriage.

Just then, his father hobbled around the corner of the house, carrying a couple of planks under his arm.

"You watch yoself round them white folks, son. Just take in the clothes, git what they owes ya and git on way from em. Ma'am Paula'll make ya wait fore she gives ya the money. And all the time she'll have it in her pocket. But she likes to do that. Make ya have to wait for her. But don't say nothin. She'll think ya bein sassy." He stood the wood against the side of the house then rubbed his hands together. "I hates them damned crackers. I hates their fuckin guts."

"Hush that kinda talk round this boy," his wife interjected. "He don't need to be hearin nothin bout no hate."

Chester fired a resentful glare at her, then chuckled and showed the empty space in the middle of his top row of teeth.

"I'm tellin this boy what he needs to know in order to survive in this man's world, in this here year of nineteen-thirty. These peckers is out to see us dead. Don't ya realize that, woman?"

"Maybe the world ain't like this everywhere," Holly said. "This is Georgia. Everywhere ain't like Georgia. It ain't like this up north."

"Like hell it ain't. It's like this wherever there's white folks." Chester turned and fixed a stare directly on Wesley.

The boy became still, except for the tremor in his limbs. Again the hot feeling rushed through him, stirring his bladder. His stomach felt hollow. His father's threatening talks always upset him. It was all a part of life he didn't exactly understand. But he understood there was a certain way he was expected to behave around the whites who in all instances had more of everything than the blacks and could tell them what to do.

"I just don't want no trouble with none of these damned peckerwoods," Chester grumbled on. "I wants Wesley to be sure he knows how to act when he's gotta be round em. We done had enough trouble."

"Lord, have mercy," Holly proclaimed, raising her hands in reverent surrender to the high blue sky.

Wesley's joints suddenly felt stiff as he pulled the wagon over to the table. A hot tightness seemed to be binding his brain while sweat seeped from his armpits, soaking his tattered shirt. He knew why his father talked the mean way he did. A group of white men had come to their house one night several years before and accused Wesley's older brother, Nathaniel, of stealing some whiskey and talking fresh to a white woman on the street in town. They barged in the front door, led by Mr. George, the brawny owner of the general store down by the railroad tracks, and ordered Holly to leave the room while they interrogated Nathaniel, then proceeded to beat him unmercifully with rubber hoses and pieces of stove wood.

Having been barely four years old at the time, Wesley had hidden under his parents' bed, too afraid to cry, cringing and pissing while the heavy boots stomped and the angry white men's voices called for murder. The worst happened when Chester protested the beating of Nathaniel, thereby sending Mr. George flying into a rage wherein he ordered the men to tear off Chester's pants and hold him down on the bed to be whipped across the ass with a section of bridle harness. His struggles were easily vanquished by the brutal men, and for the finale, he got knocked numb by a big fist in the jaw. Wesley could never forget the way his daddy had whooped and hollered and how the bed shook every time Mr. George laid on one of his lashes.

"You lucky I don't hang yo black asses," the store owner had ranted. "You niggas better start knowin yo place. And you better always have respect for a white woman. That's the one thing you better never forget as long as you live."

Holly had cried for a long time after the intruders left their home, and she got down on her knees and prayed out loud to the Lord.

"Awright, Wesley," Chester roared. "Stop that daydreamin and git the lead out."

Wesley snapped back at the sound of his father's voice and yanked the rope handle on the wagon. He parked it alongside the table and proceeded to load the clothes into wicker baskets.

"I know what I'm tellin the boy is right," his daddy lectured on. "He don't need to be like his brother, bringin trouble up in here then havin to run off to live in Atlanta. White folks ain't nobody to be messin with."

Wesley felt weak in the knees as a curdled taste filled his mouth. He hoped his father would stop talking about the white people and his brother.

"Ya don't give them damned Kents no sass. Ya hear me, Wesley? And always keep yo eyes off them white gals. Don't ya look at em no kinda way. Keep yo little eyes on the ground. One of the quickest ways for ya to git in trouble is to git caught lookin at a white gal. That thang tween their legs ain't for you."

"Stop it, Chester," Holly chimed in again. "Wesley's just made eleven years old. He ain't thinkin bout no gals. No kinda gals." Her mouth wrenched into a scowl and her chin started quivering.

"What's the matter with you, woman?" Chester limped over to the steaming pot. Holly picked up some soiled linen and tossed it into the water. He grabbed her arm, but she jerked away.

"That kinda talk ain't no good in front of the child, Chester. You'll make him scared to death of white folks. He's already fearful enough as it is. He's still wettin the bed at his age. And ya see how he's afraid of the dark."

"It ain't a matter of him just bein scared." Chester hawked and spit out his words, making the veins bulge in his sweaty, brown neck. "I wants him to know just how mean them suckers can git. My leg ain't never gonna be right again behind them crates fallin on me at that old damned Meacham's Lumber Mill. That old foreman, Mr. Harry, won't let me work no mo. And it was all his fault them crates fell in the first place. I can't help our boy no mo if he gets in trouble. I can't even run fast. He gotta know what he can and can't do here in Calhoun County. I learnt and my daddy learnt. Now Wesley gotta learn. And you know the worst he can do is say somethin outa the way to one of them cracker gals. He better not even look." Chester started gritting his teeth and frothing at the corners of his mouth. "Naw, he can't even look. He's guilty just for lookin. Mr. George coulda took Nathaniel out and hung him for speakin and winkin at Miss Ford that time. Ya know that, Holly. I know you ain't no damned fool. And ya know that little sway-back hussy was leadin the boy on."

Holly didn't reply as she picked up her pole and churned the clothes around in the pot, her long arms working furiously as she summoned all her strength. The water was starting to bubble more vigorously and the steam continued to rise.

"Yeah, ya better listen to me good, Wesley," Chester began again, turning back toward the boy. "I'm tellin ya these things for yo own good. Ain't nothin you can do gainst no white folks. Not in these parts. So don't be gittin no kinda funny ideas in yo head or listenin to none of them crazy folks round here, them Communists and things. Ya hear me? And you don't be lookin at Ma'am Paula too hard when ya take them clothes over there. Everybody figures she's a good looker. She thinks so herself."

"Yes, Daddy," Wesley replied, meekly, without looking up from his loading chore.

"Leave him be Chester," Holly wailed. "Please leave him be. Things is bad enough out here in the world. Can't we at least have some peace amongst ourselves?"

Whirling around, Chester leveled his finger at his wife and slowly advanced on her, his face contorted into a monstrous expression of distemper. He hiked his belt up on his puffy belly and kicked at the dirt.

Wesley finished loading the basketsful of clothes into the wagon and picked up the rope handle. He wanted to get away before some awful calamity happened, but his legs felt weak and he felt like he wanted to pee again.

His father stopped beside his mother as she stirred the boiling laundry with all the force in her worked-out body. He muttered something Wesley couldn't hear, then suddenly he snatched the pole away from her.

"You's the biggest fool I ever seen," Holly stormed at him. "That mess with that Mr. George happened over seven years ago. That man ain't even in this county no mo. Lord, have mercy."

"Hush yo mouth, woman. All you ever do is cry to the Lord and read that damned Bible."

"You better watch yo mouth, old damned nigga, or you gonna git struck down. You's blaphemin God."

Wesley cringed and almost started to cry when it appeared as though his father might hit his mother, but the man stopped short, looming over her with the pole in one hand and his other fist drawn back.

Wesley ran around the side of the house, pulling the rumbling wagon behind him over the bumpy ground. He crossed the front yard and headed up the road, his heart beating fast, tears swelling in his eyes. A car was coming toward him, stirring up a cloud of dust. He veered off into the weeds so that the bundles wouldn't get dirty. A white man with a long neck sat hunched over the steering wheel and paid him no mind as he rolled by. Wesley took time to relieve his bladder while standing in the brush.

He paused when he came to the crossroads on the hill a little ways from his house. He turned to look back at the row of shabby shacks where he had lived all his life. His shanty was the one with the roof that dipped in the middle. He wondered whether his father had hit his mother by now. Were they fighting and tearing up the house? Or was his mother lying across the bed sobbing while his father continued with his tirade about the white folks? Wesley had witnessed many such scenes, especially since the old man's accident at the lumber mill. His father now seemed all-consumed by hot blood and rage devouring him from within.

Wesley looked both ways along the newly paved road, the first to be covered in his part of Calhoun County. Pulling the wagon was going to be faster across the smooth black turf. The late-morning sun was starting to come on strong. Sheets of heat reflected off the asphalt, shimmering before his eyes.

"Hey, Wesley," called out a voice from behind him. "Where ya goin?"

He looked around. Terrell Cooper, a boy his own age who lived in the shack across the road from his, was trudging toward him, kicking up the red Georgia dust.

Wesley twisted the rope handle tightly around his fingers and waited to greet his neighbor.

"You sure is walkin fast," Terrell said when he caught up. "Where you on yo way to?"

Wesley looked back at the loaded wagon and shrugged.

"Oh, you takin stuff to the Kent folks. Gonna git yoself some money."

"That's my momma and daddy's money."

"Can't you spend none of it?"

"Naw. My daddy'll whup me if I do."

Terrell looked down at the clothes and sneered. He was taller than Wesley, and wider in the shoulders. A challenging look rankled in his eyes. Wesley disliked him intensely, but he didn't want to say anything that might rub him the wrong way and start trouble.

"Well, you better git on along to yo folks," the boy taunted with a grin. "They probably waitin on you and lookin at their watches. My daddy don't work for no white folks no mo. He works for hisself, like I'm gonna do when I gits grown. My daddy sells whiskey. Even Sheriff Busby buy his whiskey from my daddy. And we got a car, too."

Wesley lowered his head and remained silent while the feverish sensation started building again. He could feel that Terrell wanted to do something mean to him.

Wesley turned away from the boy and stepped onto the paved road that felt hot enough to burn through the thin soles of his shoes. He didn't look back as he skipped away with the wagon wheels rolling squeakily behind him. An occasional car or truck whizzed by. A horse-drawn cart loaded with watermelons creaked past him, headed in the opposite direction. The sunburned driver smiled and waved to him with the red handkerchief he used to mop his sweaty brow.

Soon, Wesley came to the railroad tracks and stopped. The earth rumbled beneath his feet as the express train roared by, the driving rods on the wheels of the great locomotive churning furiously while the puffs of steam belched from its stack. Someday he intended to be riding in one of the dark green coaches bound for Chicago or maybe Detroit.

When the train had passed and the dust and cinders had settled, he continued on, turning off after a while onto a gravelly side road at the top of a hill, within sight of the church steeple and the courthouse in the main section of town. He scurried along, pulling the wagon again with more effort than he had across the smooth asphalt. The leaves on the branches of the great willows and magnolias shielded him occasionally from the searing rays of the sun.

White people were all around him now, relaxing in the shade on their front porches and going about their daily chores, moving sluggishly as though they commanded all the time in the world. But he moved with great haste, knowing the Kents were expecting their laundry before the morning had gone.

A queasy feeling sloshed in his belly. He had to be extra careful and do nothing to raise the ire of the people around him. Hopefully, Ma'am Paula wouldn't stall about giving him the dollar-and-a-half, the way his father had predicted.

The Kents' home sat on the right side of the road about a quarter-of-a-mile from the main thoroughfare. It was a sprawling frame house, recently painted white, with a porch that wrapped around both sides. The grass smelled freshly cut, and the neat rows of snapdragons and petunias along the fence showed meticulous care; fancy lamps stood on each side of the stone-laden walkway leading to the front door. There was a distinct aristocratic air about the place.

He approached cautiously. The little girl, Gertrude Kent, wearing a pink dress and ribbons in her hair, was playing with her dolls in the front yard under a fig tree.

"Hello, Wesley," she said, pleasantly.

"Mornin, Missy." He forced a smile and cast only a quick glance in her direction.

Nelson Kent stood at the door, seemingly staring right through Wesley. He was a hulking man with an extruding lower jaw and a bristly moustache that obscured his top lip. His blue eyes projected something cold and sinister. Wesley stepped up his pace so that he could hurry up and get away from him.

A breeze came, making the trees swing and sway as he scampered around to the rear of the house. He stopped suddenly when one of the Kents' dogs, a husky shepherd with blazing eyes, ran toward him, barking and snapping. The animal came in close and began circling Wesley, holding its head low and showing its teeth. Wesley stood very still, not at all sure what he should do if the real attack came. He had always been afraid of dogs.

"Come here, Butch," shouted a young male voice. "Leave that boy alone. Get on away from him."

Wesley looked around just as Donald Kent, the oldest boy, ambled up and drew the dog's attention by clapping his hands.

"That ain't nobody but little Wesley," Donald drawled as the dog jumped up and nipped playfully at his master's fingertips. "Leave him alone. He's just a fraidy cat like his ol cripple pa."

The remark made Wesley wince. He started to move away, but something in the white boy's eyes forced him to keep still. The quivering started in his limbs. What had he done wrong? What did Donald Kent want?

Then suddenly it dawned on him. "Thank you, Master Donald. Thank you, thank you," he said, nodding the way he had seen his father and the other black men do.

"Awright, Wesley. But you be sure you don't mess with old Butch again." Donald Kent rubbed the dog's head and grinned. "Now you better scat. My momma's waitin for them clean clothes."

Wesley hurried around to the rear of the house and parked his wagon, then stepped up to knock timidly on the kitchen door. Music was playing on the radio somewhere inside; something sweet was cooking on the stove. But no one answered. Again he rapped softly on the wood.

Presently, Paula Kent came to the door. A tall, busty woman with copper-colored hair and keen features, she carried herself in a haughty manner, head held high, her pinched nose turned up as though she detected an odd aroma. Patches of freckles dotted her cheeks. Wesley always felt tense and awkward in her presence.

"It's about time you got here, boy." She flicked the hook on the screen door and pushed it open. "Bring the clothes in and put them over there." She stood aside and pointed to a long table. "And hurry up now."

"Yes, Ma'am." Wesley didn't dare look into her eyes as he stepped into the kitchen.

"Git the clothes first, boy," she snapped. "Where's your mind today?"

"Oh, yes, Ma'am," he said, feeling foolish for having rushed in empty handed.

"And don't you let any flies in this house."

"Yes, Ma'am."

He stumbled clumsily over his own feet, but managed to keep from falling as he hurried back to the wagon. Moving quickly, he made three trips back and forth carrying the bundles into the kitchen and stacking them neatly on the table. He looked around for Paula Kent when he was done, but she had gone.

Sighing dejectedly, he went outside and flopped down in his wagon. His father had told him right. He was going to have to wait for her to give him the money. Hopefully, she wouldn't hold him up for long.

A dull, throbbing ache started around his temples while his stomach groaned and twisted. His mother would most likely have some lunch ready when he got back home. He hadn't eaten any breakfast. A couple of crows were perched on the picket fence separating the Kents' domain from their neighbors'. He imagined that the birds were laughing at him when they started their raucous chatter.

He felt small sitting in the shadow of the grand house where Nelson and Paula Kent carried on with their charmed lives, far removed from underlings like himself. Had circumstances always been this way between people? he wondered. Would they always be this way? The things his father said about the white people always turned out to be true. Frighteningly true. But why didn't his mother want him to hear his father's words? Why did they argue so much? It was all too confusing.

His thoughts drifted away to grape jelly and bread. That was what he wanted when he got back home. And a tall, cold glass of milk, or maybe some iced tea. He looked at his wagon. It was time for a new one. He would start working on it right away. Maybe he could find some wheels near the dump on the east side of town.

In a little while Paula Kent came to the door again. He stood up, but still kept his eyes down as the tingly feeling returned to his limbs.

"Come and get your money, Wesley." She cracked the screen a bit and held out a paper dollar and a coin for him.

He went and received the cash and slipped it into his pocket. "Thank you, Ma'am."

"Wesley," she said, as she was about to turn away.

"Yes, Ma'am?"

"Want to make yourself a quarter?"

An upsweep of jubilation made him raise his head.

"There's a pile of old clothes and things I want cleaned up in the cellar. They've started to mildew. The whole cellar flooded last week when we got all that rain. You can move the stuff off the floor and put it in the barrels you'll find down there."

Wesley nodded and grimaced when his empty belly groused again. His gaze focused on Paula Kent's smooth, pink hands and the glittering diamond ring she wore on her finger.

"Now come on and I'll show you the cellar and what needs to be done."

"Yes, Ma'am."

He followed her across the kitchen and into a cluttered pantry where the shelves were lined with jars and cans of fruits and vegetables. She moved with a lilting spring in her step, her flowing blue dress showing off the curves of her hips. He caught a whiff of her perfume. She opened a door inside the pantry and reached in to turn on the light.

"All right, Wesley." She stood back, pointing to the broken staircase descending into the cellar. "You'll find a bunch of stuff piled in a corner down there. Just take it and put it in the barrels like I told you. There's a shovel down there you can use. And you be careful going up and down. I don't know when Mr. Kent's going to be finished fixing the steps. He's been working on them for the longest. At least he ran a wire down there so there's some light."

Wesley paused at the top of the stairs and peered down into the gloom. A musty, rotten odor came forth. The staircase was rickety and a couple of the steps near the top were missing, enabling him to see through to the floor.

"Don't be afraid, Wesley. There's nothing down there but maybe a squirrel or some field mice that might've got in. But they'll be long gone once you start making a little noise."

He cleared his throat and sighed, "Okay," then started down, holding onto the rail, which was still loose from the wall. When he was a step away from the cellar floor, he turned to look back. Paula Kent had gone. Hopefully, he wouldn't have to wait long for his money after he finished the job.

The air felt damp and chilly. Bitchballs and cobwebs obscured the holes and cracks. Tools and sections of pipe were scattered about. A riding saddle, decorated with rhinestones and fancy straps, was resting on a stack of old newspapers and magazines.

A low groan seeped from between his teeth as he surveyed the unpleasantness of his new job. He could've refused the work, but that might've implied sassiness on his part, and his father and mother had warned him about the consequences of such expressions.

Sighing longingly, he turned and reached for the shovel leaning against the wall. For a moment he thought he might drop into a heap when a nauseous sensation ignited somewhere deep inside him. He didn't want to be stuck in the Kents' cellar working with filth while a glorious summer day raged above him.

He let the heavy shovel clank across the floor as he dragged it over to the pile. Old clothes, newspapers, and numerous other discards were packed and held together by the muck. He worked slowly but steadily, scooping up the smelly debris and tossing it into the barrel.

After a while, he decided to take a rest and wipe away the sweat. He assessed the work remaining to be done. There wasn't much. Soon he would be finished and on his way to buy something he wanted with his own money.

He went and sat down under the stairs on an old steamer trunk that was rusted around the latches and hinges. Something bumped across the floor overhead, then the dog barked outside. Wesley slumped his shoulders and stretched his legs. The solitude of the cellar seemed to be creeping over him and settling in his bones. And he appreciated the seclusion he had inadvertently stumbled upon. The antagonists in his world were busy with other things, freeing him for a short time from their wrathful badgering and scrutiny. His thoughts wandered from place to place in his life, lingering now and then on his father and mother, the house, the characters, the Georgia sun and the red clay. He used the toe of his shoe to make an aimless design in the dust. Maybe he should buy a new pack of marbles. Terrell had beaten him a few days before and captured his best cat's eyes.

The clopping of footsteps startled him out of his repose. He looked up. Miss Paula's dress made a rustling sound as she started down the stairs. Then she stopped and turned around to speak to someone. "Take the seeds and put them in the shed, Joe."

Wesley's eyes opened wide as he stared up through the space where the plank was missing in the staircase. Miss Paula was standing directly above him, straddling the opening and presenting him a clear view of what was underneath her dress and petticoat.

She was wearing split drawers, which left the cleft between her thighs uncovered. A tuft of auburn hair bristled over the apex of her gap and blended out to a ring of fuzz around the cheeks of her rump. The flesh just inside the lips of her opening looked moist and pink, resembling a huge eye that stared down accusingly at him.

A scalding sensation erupted somewhere inside his brain and flowed down into his eyes. He dared not move. He was looking at something ominous and terrible; something he had no business seeing. But he didn't want to see. He hadn't asked to see. Suddenly, he couldn't breathe, and he was thrown into an inner frenzy as surging emotions he didn't' comprehend upset the fragile balance in his fretful world.

"Bring those boxes down here," Miss Paula ordered, continuing her descent. At the same time, Wesley let out a blood-curdling scream as the fire flared up in his eyes and cut off his sight, sending him first into brilliance, then into darkness. He started crying and blundering around, bumping into the stairs and the wall, hoping somehow to blink the right way and bring back his vision. But nothingness prevailed.

"What's the matter with you, boy?" Miss Paula stood on the bottom step, her scrunching brow expressing her befuddlement.

Wesley moved away from the sound of her voice. Were there others with her? Did she know what he had seen? He trembled and quaked, and his knees gave way as he sagged to the floor. His thinking went blank while in his mind's eye he saw angry white faces swirling around him. His father's mauling, punitive voice rumbled in the background, accusing him of a gross impropriety.

"What's wrong, Wesley?" Miss Paula questioned, impatiently. "Did you fall? I told you to be careful. Don't you hear me talking to you?"

But he didn't hear her. Couldn't hear her. He was too wrapped up in the wrathful ball of fire. He had been struck blind, and he was now about to be set upon by the powerful villains that ruled his world.

"Don't beat my daddy," he whimpered. "Please don't beat my daddy. I didn't mean to look."

Paula Kent and a scruffy-looking white man wearing patched work clothes stood over Wesley.

"What's he talking about?" she asked, more to some invisible fourth party than to the scruffy man.

"Maybe he's havin some kinda fit," the man replied, churning a wad of tobacco around in his mouth, his drawling words sounding like mush.

Wesley recoiled and gasped when firm hands finally lifted him and carried him upstairs. Was he being taken out to be whipped? Or were they going to hang him? His eyes were open, but still unseeing. The sounds and voices around him became incoherent and disconnected. What was this thing he had seen between Miss Paula's legs?

Not knowing anything else to do for the child, Paula Kent spread a cold towel across his forehead as he lay sobbing on the seat in the foyer. Nelson Kent looked in on him, but was too occupied with newspaper business to become involved. "Those damned people are always having some kind of spell or seizure," he said, scornfully, while glaring down at the quivering child. "You better send for his folks so they can come and get his ass out of here."

What seemed like several hours to Wesley passed while he shielded his face with his arms and languished in a state of numbing fear where the slightest noise made him think of impending calamity. He felt sick to his stomach a couple of times, and broke out into a sweat. Paula Kent called him a "sickly little black rascal" when he peed on himself and the urine soaked through his pants and made a spot on the seat.

He started crying again when he finally heard his daddy's grumbling voice. "Where is he, Ma'am Paula? What's done happened to our son?"

Wesley knew his mother was there, too. He reached out for her, and sure enough she was there to embrace him and rub his head.

"I can't see, Momma," he sobbed again and again, hoping she would hurry up and get him out of there before someone found out the truth about what he had seen.

"I don't know what happened to him," Paula Kent declared. "We found him stumbling around in the cellar talking about how he couldn't see."

"We thanks ya for sendin for us, Ma'am Paula," Chester said. "We's gonna git Wesley on home so Doc Hayes can take a look at him."

"My seat is ruined," Paula Kent said, disgustedly, after Holly had coaxed Wesley to stand.

"I'll clean it for ya, Ma'am," Holly told her, most sincerely. "I'll come first thing in the mornin and scrub it real good. Don't you worry none. I'll git all that weewee off of there."

Chester paid a man he knew named Walter to drive them home in an old blue pickup truck. They all sat cramped in the front cab, Wesley on his mother's lap leaning his head against her shoulder. No one said a word during the short, bumpy ride.

Wesley's sudden blindness baffled everyone. He claimed he couldn't remember what happened to him in the cellar. Both his grandmothers came to see him, and they talked in whispers with Chester and Holly.

Dr. Hayes, a bony, stooped-over man, stopped by the house later that same evening and looked him over, but contended that he couldn't find anything wrong, especially with his eyes. He speculated that Wesley may have fallen down the Kents' staircase and banged his head. But the doctor couldn't wholeheartedly support his own theory since he could find no cuts or bruises anywhere on the boy.

"My baby done been struck blind!" Holly shrieked as she and Chester sat in the kitchen listening to the puny country doctor deliver his vague diagnosis, and suggesting finally that Wesley be taken to a specialist in Atlanta, whenever they could raise the money, and advising that in the meantime the boy should get plenty of rest and drink hot tea.

A morbid cloud fell upon the Sledge home after Wesley came down with his affliction. Over the next few days, he spent most of his time sitting on the porch listening to the familiar sounds he had always taken for granted. Neighbors came bringing fruits and candies, but unbeknownst to them, their approaching footsteps and voices always caused him dreadful attacks of anguish and terror. He still believed that somehow it would become known how he had seen under Miss Paula's dress, thereby inciting the white men to inflict suffering on him and his daddy as they had done a few years before.

Chester blamed the Kents for Wesley's sudden handicap, maintaining that they had knowingly sent the boy down into an unsafe situation. He started spending more time away from home, and would stumble in late at night, reeking of moonshine, grumbling and mumbling to Holly about the bleakness of their situation in the world, cursing the Kents and all the other white people in the county. Wesley would be lying awake in bed, listening and trembling, sometimes crying softly while squeezing his fists against his eyes. Holly made sure that Chester didn't find out the boy was wetting the bed almost every other night.

Wesley felt safest when he and his mother were at home alone. She would cuddle him and tell him silly fables about the small animals that resided in the woods, carrying on their lives in human fashion. He loved these stories wherein his mother would affect different voices for the possums, raccoons, ducks and hounds. Then she might sing to him while keeping the beat with her tapping foot and thumping fingers.

"Momma, will I stay blind forever?" he asked one evening while a gentle rain pattered against the windows.

Holly stroked his head and sighed. "Only the good Lord knows, Wesley. We just have to put our trust in Him to see us through this ordeal."

A terrible ache built up in his chest. He wanted to confess his crime, or sin, to the only person in the world he could trust. It wouldn't hurt him and his daddy if she were the only one who knew.

He sat close to her on the bed with his head lying against her breast, inhaling the fragrance of the talcum powder she dusted on every morning.

"Yo daddy's gonna git that money we needs to take ya to that special doctor in Atlanta," she said. "I'm startin to do some sewin for the Killebrews tomorrow. We'll git ya there, son. We'll git ya there."

He kept silent for a long time. The rain started coming down harder and the wind shook the whole house. No one was going to knock on the door for a while. His father was most likely getting drunk at the liquor house and wouldn't be home for a long time. Wesley wanted to tell his mother what he had seen. Surely, she wouldn't scorn him.

"Momma," he mumbled finally.

"Yes, son."

"It's somethin I gotta tell ya bout Ma'am Kent and what happened in the cellar."

Holly tried to make him sit up, but he buried his face deeper between her breasts, almost smothering his voice, and she allowed him to remain there while caressing him behind the ear.

"Momma, I'm scared."

"Ain't nothin for ya to be scared of. Ain't nobody here but you and me."

His heart was starting to beat fast. He opened his eyes and strained to see beyond the blackness, but there was still no sign of light.

"Come on and tell me," she urged. "What happened in that cellar? It's been two weeks since it happened. Ya can talk about it now."

"I seen somethin bad." The tears were building again. "Somethin real, real bad."

"What, Wesley?"

"It was Ma'am Paula," he moaned, his teeth chattering. "I didn't mean to see. I didn't mean to look, Momma."

"What did ya see, son? Tell me. What did ya see?"

"Oh, Momma, I was sittin under the steps in that cellar and I could see straight up to the ceilin. There wasn't no boards in the steps. Then Ma'am Paula come and stand right over where I was and I seen straight up under her dress. I seen what daddy and everybody say I shouldn't see. I seen her thang, Momma. I seen it."

"Wesley, Wesley. It's awright. Ya hear? It's awright. Don't be scared."

"They gonna come and beat me and daddy," he cried. "They gonna hang us, Momma. God struck me cause I done bad and seen it."

"Naw, naw." Holly held him close so that his tears soaked the front of her dress. "Ain't nobody comin here and doin nothin to us. Not a thang. Ya hear?"

"But, Momma. I seen it. I seen it."

"What did ya see, Wesley? What did ya really see? You ain't seen nothin but some old white woman's behind."

He sat on the side of the bed, shoulders squeezed in his mother's tight grasp, his gaze vacant and seemingly fixed upon some abstract symbol very far away. His thoughts linked up with his vocal centers and tried to come up with an answer to his mother's inquiry. What, indeed, had he seen? What was that patch of hairy, perforated flesh? All women and girls had one of them, as he understood the way the Lord made people.

He never answered his mother. Instead, he drifted off to sleep and remained in a state of peaceful slumber throughout the night.

A clamorous rattling of pots and pans in the kitchen startled him awake the next morning. He sat up in bed and gasped as the sunlight blazed through the windows, making him squint as he opened his eyes in wonder.

"Momma!" he shouted, leaping up and running into the kitchen. "I can see again, Momma. I can see."