Home

Excerpts from:

There Ain't No Justice, Just Us

A Proletarian Novel by Gregory Alan Norton

There Ain't No Justice, Just Us is the fictionalized account of real wildcat strike that took place in South Chicago in 1979 at a Lard Factory. Mexican and African American factory workers united together to fight the company, their corrupt union, the police, and others despite the fact that these two groups had frequently fought each other in the neighborhood prior to this strike. "The Dwarf" in the story refers to a real Chicago cop who has since been exposed as torturing many minority prisoners into "confessions." I like this part of the story because the women in the neighborhood supported the men and blocked a train from entering the factory. As a life-long factory worker myself, I was fascinated when I did the research for this novel, and got to talk to some of these working class heroes. Lots of the people involved had a real historical sense about this battle - first, that it was their turn in history to put up a fight, and second, so many of them had a sense that they were battling for a much better, democratic, working-class society of the future. I found it an honor and privilege to try to record their story.

The story begins with a corrupt union local that tampers with a contract vote. To avoid a strike, union officials and the company collude to stuff the ballot box with "yes" votes for a terrible contract. -- Gregory Alan Norton

From

Chapter 7

Ken Williams

(an African American shop floor leader -- G.N.) posted his open letter

bright and early the morning of June 8. Neatly printed; it read:

"This

is an appeal to all employees of Chicago Lard Corporation. As you know we

were shafted by the union. On June 6 we were gather together to vote on the

acceptance or rejection of a 3 yrs contract. Our so call union official fail

to interpret the contract completely. The Voting procedure was most definitely

a fraud. To my knowledge this meeting was supposed to take place on June 7.

Our union steward knew all along what day the voting would take place but

fail to advise us, (the employees) for reason I will not reveal at the present

time.

"The

use of psychology is most definitely in full play among our superiors toward

us, but there are still a few of us who have the knowledge of its use. I make

a plead to you to stand up for what you know is right. Its time to challenge

these imperialistic minded higher up and put an end to this childish game.

Any question regarding the above said information will be answered."

Ken plastered

the factory bulletin boards with the letter long before most of the people

had shown up for first shift. We met in the early morning sunshine, out by

the IC railroad tracks. It was going to be a hot day. The parking lot was

dusty. At 7 A.M., we had 39 out of a total of 42 workers. Once again, technically,

we'd gone on a wildcat strike because all the young guys on third shift were

out in the parking lot instead of tending the machines in the factory. Only

Joe Grabowski was noticeably absent.

Ken passed

around additional photocopies of his letter. Juan Diaz agreed to translate

the conversations. Compared to our other outdoor meeting, this one went very

smoothly, probably because of the early hour and definitely because we were

all in obvious agreement that we'd been screwed. It began to dawn on me that

these guys were suddenly putting all the sadistic teasing and violent arguing

behind them. The riffs between the Mexicans and African Americans began to

disappear. The big cultural gap between the older African American workers

who grew up in Dixie vs the younger ones who'd only known Chicago also appeared

to be closing. People who characteristically wouldn't talk to each other except

to annoy one another were now sharing a common cause. Suddenly, they were

all in the same situation and the were all pissed. Harold Crown, Chicago Lard,

and Local 55 of the Amalgamated Chicken Union had finally gone too far.

Swiftly,

they agreed to strike unless another vote was taken. They set the strike date

for Monday, June 12. Ken suggested electing a three-person leadership committee.

Nobody argued. Juan Diaz nominated Robert Morales. He was unanimously elected.

Early nominated Ken. He was unanimously elected. Engleman nominated me, and

I, too, was unanimously elected.

By 8 A.M.,

we were in Crown's office. He looked tired and groggy. Characteristically,

he wore a crisp short sleeve white shirt and solid black tie. I could tell

he just wanted to fire all three of us, and it was with a great effort that

he seemed to rein in his temper. We reminded him of our petition which virtually

everyone except Joe Grabowski had signed demanding the revote.

He reminded

us that he'd no control over "our" union and stuck to his contention

that the whole thing was out of his hands. He reiterated that we had to honor

a legally binding contract for the next three years.

Ken did most of the talking for us, and he insisted that we weren't going to put up with an obviously rigged vote.

Roberto

didn't make any points of his own, but when Ken or I said something he liked,

he pitched in and said, "That's right. That's what we all want."

Crown kept telling us that our complaint was with our "own" union,

not with him.

"Well,

Mr. Crown, we'd appreciate it if you'd use your influence with 'our"

union to get them to come down here and talk to us," I said.

Crown

frowned at me, but agreed to do just that. I could tell Crown was developing

an active distaste for me, probably similar to the one he'd developed over

the years for Engleman. What apparently astonished Crown was my ability to

get to the top of the shit list so quickly. I thought he actually blinked

in surprise when I walked into this office. He obviously had anticipated John

Engleman.

"You

need to understand, Crown, that this is going to be your problem if we shut

this factory down," Ken Williams said.

"I'll

see what I can do as far as getting your union representatives down here.

But I don't think I need to remind you that any labor action you may take

would be strictly illegal. And if anyone walks off the job here, that person

is going to be discharged fro the employ of the company. Am I making myself

clear, gentlemen?"

"And

if we don't get to vote on the contract again, we're going to shut this place

DOWN. Am I making myself clear?" Ken said.

Crown

put his hands up in front of his face palms out. "I think we're finished."

We marched

out of the front office, the secretaries and bosses like Melvin watching us

with open curiosity. We took the stairway that led to the filing line. In

the noise, commotion, heat, and stench of the shop floor, I asked Ken what

he thought. Roberto had already walked away to talk to a couple of forklift

drivers about the results of the confrontation. Everyone was watching us talk.

"I think we're headed for a showdown."

The factory workers proceed to unite everyone, African American, Mexican, and the few white workers in the factory. When the company and union refuse to allow a fair vote on the contract, they call a strike against both the union and the company.

From

Chapter 16

Not much happened around the plant Sunday. Our remote picket line looked very thinned out. When I woke up Sunday morning in Lexy's apartment, I deliberately headed back to my South Chicago apartment. I didn't want to hang around with Lexy all day, because I knew where that would lead to. Monday brought a lot of commercial bustle to the neighborhood. We found it virtually impossible to picket and obey the injunction. We wound up milling around the neighborhood and our morale began to sink as we watched scabs coming and going unmolested.

Some of

the guys left the picket line when trucks arrived and pulled into the dock

without a problem. The Illinois Central ran a train down the track and switched

out a tank car.

Ken and

I agreed that the train switch had been a hoax. Neither one of us thought

that the tanker was full. Ken told me that he thought we were headed for problems.

"What

problems?"

"Two

of the deodorizer operators are beginning to waffle on us. They want to go

back. They're broke."

"How

much longer do you think they'll stay out?"

"No

telling. Crown phones them every night. He's offering them better pay, and

better benefits than the others."

"He

can't do that. It's a violation of the union contract."

"Union

contract only provides for the minimum a company must provide. If a company

offers somebody more, the union ain't gonna fight it. The rest of us have

a grievance, then, for discrimination. But we have to go file our grievance

and fight it through channels."

We held

a very turbulent meeting in our union hall on Monday night. I noticed our

numbers at our meetings were dwindling, too. People were losing hope. I knew

we needed some kind of emotional boost, but I felt burnt out, completely weary

of the protracted fight. I remained silent when Engleman got up to speak.

"You

guys are chickenshit. You gotta beat up the scabs. You can't let them go in

there and run the fucking factory."

"I

don't see you jumpin' on anybody," said Earl.

"We

all gotta do it together. Let's go out there tomorrow and kick some ass,"

said Engle-man.

Juan Diaz translated all that, but nobody, black or Mexican seemed eager to

pick up on Engleman's challenge. Nobody wanted to meet the dwarf. Nobody wanted

to get locked up down at 26th and California, in Cook County Jail.

Then Cecelia

spoke out. She complained of inaccurate translations by Juan, and then proceeded

to translate her

own words. The Mexican workers didn't display much of a reaction when she

asked that one of our Puerto Rican supporters do the translating. She asked

for "better translations" whatever that meant. She put that to the

vote in Spanish and they all agreed includ-ing Juan, who apparently was tired

of translating. I wondered if he was trying to hide things from the other

Mexican workers, or if he simply wasn't any good at translating. One thing

was for cer-tain, he seemed happy to be out of the limelight.

I thought

Cecelia had finished when she got the translating switched over, but she wasn't.

She held the floor while Juan sat down and the young Puerto Rican guy came

up to the front. "You men can't quit now. If you don't ignore this injunction,

Crown is going to win. I'm ashamed of you all. Tomorrow, I'm going to go sit

on those damn railroad tracks and keep the trains out. We can't allow the

railroad to do anymore switching. Crown is shipping out every last once of

product he's got stored in his warehouse. So, come on, now." Her voice

reached a high pitched crescendo when she finished. She was genuinely angry

at us.

Nobody

knew what to make of that. Lexy told me later that she intended to come down

to the factory Tuesday morning. She thought there was going to be trouble.

I didn't know what to say to Cecelia. I wasn't sure if the injunction would

apply to her or not. For sure she would lose her job, when she came out of

hiding in the office and took a position on the picket line. We would lose

our number one inside source on what was happening within the factory, and

I hoped whatever boost we got on the picket lines would offset the loss of

our spy.

Tuesday

morning Cecelia was as good as her word. She didn't go into work that day.

She told us some of the other Mexican secretaries wanted to "go on strike"

with her, too, but Cecelia made them stay inside as our future conduits of

information. The minute she appeared on the picket line, of course, she lost

her job, because she wasn't in the union's "bargaining unit." Some

of the guys who had abandoned the picket lines and had begun staying at home

showed up after hearing about Cecelia's previous evening's threat.

Cecelia

had brought two neighborhood women with her, one of whom had a baby and a

toddler with her. Almost as if on cue, we heard an IC switch engine approaching

from the north. Resolutely, Cecelia and the two women sat down on the IC tracks.

The toddler sat next to her mother while she held the baby. It was probably

the most astonishing thing any of us had ever seen. The women sat in the middle

of the street with a sun umbrella over them. They could have been spending

the day on a Lake Michigan beach. The train slowed and halted north of 91st

Street. In a minute Harold Crown came storming out of the factory, followed

by Melvin who was still limping along on crutches.

"What's

the meaning of this," Crown yelled, sounding out of control, hysterical.

Crown held a piece of paper in his hands. He was yelling incoherently, a lake

breeze playing with his tie, occasionally whipping it up into his face. We

started laughing when we realized he was reading and screaming the words of

the injunction at the three women.

The spectacle drew our far flung "picket line" in close to the "no-go"

zone, and the cops clustered in tighter as an instinctive response and in

order to hear what was being said. At this point the workers were blocking

the tracks north of where the women sat, in the middle of 91st Street. We

started chanting, "Hell, no, we won't go."

Crown screamed at Cecelia, "You're fired."

"Fuck

you, I don't care," Cecelia yelled back. Crown looked dumbstruck. He

was unaccus-tomed to having his well mannered secretary shout profanities

at him.

A grey

haired cop wearing an officer's white hat approached Crown and the small group

of women. He was puffing on a pipe. He said, "Can't we settle this with

a discussion?"

"DISCUSSION?

ARREST THEM. They're all in violation of a court order," Crown screamed.

The cops moved in on us. They asked the women to move. They refused. They

told the women if they didn't move they would be arrested. Crown urged the

cops to proceed. The cop with the pipe talked into his radio and asked for

some police women to come up front.

At that

point we had clustered into the middle of the street directly behind the women.

The cops stood in their line at arm's length from us. The confrontation had

developed into the closest encounter we had yet as a group with the Chicago

Police. When a Hispanic police woman arrived, the grey-haired pipe-smoking

cop pointed to the young mother first. Apparently his think-ing was to remove

the kids from ground zero first, because a lot of ugly exchanges were going

on between the strikers and the cops.

The police

woman grabbed the young mother by the armpit, planted her legs far apart,

then hauled the young woman up. In order to grab her toddler's hand, the young

mother slightly loosened her grip on her baby. The police woman immediately

snatched the baby.

That provoked

an angry response from our ranks. The distance between our two lines disappeared,

and, in fact, some of the young black guys had somehow insinuated themselves

between the police woman and her escape route.

"Give

the baby to the father." I turned and saw Juan pushing forward a young

first shift Mexican worker who worked on the mixers. "This is the father.

Give the baby to the father." He repeated, sounding both reasonable and

authoritative.

The guys

started chanting, "Give up the baby. Give up the baby."

"I'm

gonna put this little bastard in a juvenile home." The police woman yelled

that in Spanish. So, most of us weren't positive about what was going on.

But the Mexican workers all stepped up then, and I thought for sure we were

headed for a big street fight. Juan yelled in English, "She says she's

gonna put the baby in jail."

"No

she's not, said the grey haired cop. He took the baby out of the police woman's

arms and handed her to Juan, who promptly handed her to her father. The police

woman acted plainly disgusted with the pipe smoker's liberalism, and hauled

off the young mother to a waiting prisoner wagon.

The toddler

wanted to follow her mother, but Juan wisely snatched her up, too, before

the next police woman could do anything.

"What

about this baby," John Graves yelled, "You motherfuckers gonna arrest

her, too? You got cuffs small enough to fit the baby?"

"All

right, old timer, that's enough for you. Are you trying to start a riot?"

The pipe smoker pointed to John and two cops arrested him next. It had become

clear to us whoever this guy pointed to got arrested next.

"You

motherfuckers, turn me the fuck loose," John yelled as he was escorted

toward another prisoner wagon. The pipe pointed to the other woman sitting

next to Cecelia. The police women roughly hauled up the other young Mexican

woman and shoved her in the direction of the waiting wagon.

"You

come down and bail me, Earl. You hear me Earl, goddamnit? You come down and

bail my ass," John yelled. We heard his plaintiff wails fade away over

the police ranks as he was stuffed into the wagon.

The pipe

pointed to Cecelia. The police women acted especially rough with Cecelia.

One of the black police women viciously yanked Cecelia's long hair. It seemed

to me that the police women were trying to live up to the brutal standards

of the Chicago Police in front of the men. Those standards had been set in

places like Haymarket Square, 118th and Burly during the Memorial Day Massacre,

and in front of the Hilton Hotel on Michigan Avenue during the 1968 Chicago

Democratic Convention.

"Hey,

take it easy with her. She's not resisting." I yelled.

The pipe pointed to me next. "What?" I yelled. "What the fuck did I do?" Two cops muscled me right out of our ranks. They searched me before throwing me in with John. The cops had managed to bang John's head somehow. The back of his head was bloody, and he was a little woozy.

"Oh,

man. Now what?" said John as he held his head on the wild ride down to

the Fourth District station house. John acted completely despondent.

"We

meet the dwarf," I responded.

They hauled

us out of the wagon into a police parking lot surrounded by ten foot tall

chain link fence which was topped off with three strands of concertina razor

wire. I protested John's condition and demanded they take him to a hospital.

The cops hustled us down a flight of cement stairs into the station house.

Cecelia told me later that the women had been locked in an empty room. They

cuffed me and John to a bench in the hallway. From the direction of the reception

area I could catch snatches of Lexy's voice. John kept repeating over and

over, "Oh, man. Now what." I wondered how hard he had hit his head.

Eventually, the cops pulled us down to the receiving area.

Harold Crown, Don Hacker, and Lexy awaited us there. Crown and Hacker consulted

with the cops for along time before eventually approaching Lexy. The cops

informed Lexy that every-one had been booked for "disorderly conduct."

Lexy turned

to me and said loudly, "They don't want to test the injunction."

"Just

get us the hell outta here," said John Graves.

Hacker

and Crown left. Lexy noted that they had set us up with a court appearance

with the same judge who had issued the injunction. Lexy went to work with

the cops and their moun-tain of paperwork. First she bailed the two Mexican

women. The young mother walked out the front door just as her husband was

walking in. They embraced and departed. Then Lexy bailed

Cecelia

who waited with us. Then Lexy bailed me. But she couldn't bail John. John

didn't have any identification on him. He claimed the cops had lifted his

wallet when they pummeled him on the street.

Lexy and

the cops went back and forth for well over an hour. Finally, sensing they

had the upper hand, the cops hauled John off to the dungeon to meet the dwarf.

"Get me outta here. Don't let 'em take me to Cook County," said

John. I thought he sounded pretty upset. Lexy kept banging away at the paperwork,

but the cops kept finding additional technical problems that prevented bailing

him.

Finally,

Lexy gave up and she, Cecelia, and I drove over to John's rented house in

"the Bush" neighborhood, a Victorian slum that had been erected

to house workers for U.S. Steel. We found the decrepit two story frame house

without a problem. Lexy and Cecelia went in. They said John's wife wasn't

very cooperative, but eventually did provide enough of the necessary documen-tation

that Lexy needed. The wife didn't want to accompany us to our next stop, Chicago

Police headquarters at 11th and State.

Lexy managed to get the paperwork in order after another couple of hours of bureaucratic run-arounds. They sent us back down to District 4 where we thought we would be able to bail John. We arrived back in South Chicago around sunset after fighting rush hour traffic. We were told that nobody stayed in the local lockup over night. They had already transferred their prison-ers to Cook Country Jail at 26th and California.

We drove over to the near southwest side where the jail is located and Lexy had at it with the bureaucrats again. This time we hit the wall. The best Lexy could do was set up a bail hearing in the morning. We drove back to South Chicago in a very despondent mood. Ken and most of the guys were still manning our "picket line." Nobody liked our report, although we made it clear that we had done everything we could.

We got

the bad news in the morning. Lexy and I went to bail John, so we were the

first to find out. I knew we had a problem right away when the cops escorted

us out of the receiving area where we should have bailed John. Instead we

were ushered into a luxuriant conference room where we met with some plain

clothes cops who were obviously bigshots. They told us that John had committed

suicide by hanging himself in his cell.

The cop

investigators later fed us a story that John had been depressed over his debts

and the divorce proceedings which his wife had apparently initiated. I was

convinced they had mur-dered him. The rest of that day went by in a blur.

When I got back to the picket line Ken and Earl and the guys just nodded when

I told them what had happened. Apparently, most of them had somebody in their

family or a friend who had experienced a similar fate. It was just another

day at the office for them.

The united workers had to battle against the National Labor Relations Board, the union, the company, private security cops, the Chicago Police, railroad police, and all the court actions and injunctions those groups brought against them. They had a woman lawyer who volunteered her time to help them in those fights, but ultimately the battle always came down to - could they keep the factory shut down?

From

Chapter 18

We heard

a train coming down the IC tracks. The train and the cops arrived at about

the same time. However, this time we only had fifteen workers on the picket

line and perhaps the same number of friends and relatives, mainly Mexican

people from the neighborhood. The cops arrayed well over 100 men against us.

Curiously, for the first time, they were wearing full riot gear including

helmets with visors, and special flak jackets that reminded me of the body

protectors that baseball catchers and umpires wear. Some of them in the back

ranks were fooling around with gas masks. Lots of them sported sawed-off 12

gauge pump shotguns.

Our ranks

encompassed nearly blind great-grandmothers and children.

The train

rolled up to the northern margin of 91st Street and stopped. The same old

grizzled engineer who had been present the day we faced off, Tex, stepped

down from the engine. It looked like he was wearing the same pair of greasy

bib overalls, t-shirt, red bandana, and baseball cap he'd worn the day we'd

first met him.

"Hello,"

he bellowed.

"Hello,"

we yelled back in unison.

"I

see you still got your wildcatter going, eh?"

The police

began pushing us back off the railroad tracks. They were polite and professional,

but continually asked us to move. I didn't know who were dealing with this

time, but it wasn't the labor detail. These guys looked more like a big SWAT

team. Using their overpowering numbers they gradually forced us off the tracks.

One of the cops signaled the engineer to move his train across the street

and into the factory yard. Other cops professionally stopped traffic on 91st

Street to permit the train's safe passage. Now nothing prevented the train

from entering the factory yard.

The old engineer looked over the cops then yelled, "Up yours, copper," and he flipped off the cop with an obscene gesture. To say that the cop was completely taken aback would be an understatement. The engineer yelled at us as he mounted his engine and backed up his train, "As long as you're here, we won't be. As long as you got one picket out here, I ain't crossing no picket lines."

From Chapter 19

Once again we marched into the gigantic and preposterously architecturally

imposing buildings of the Loop. The massively overbuild environment didn't

provide a humanized landscape for us. It wasn't meant to. The place was built

for those imperial citizens who own or operate it and to awe their social

opponents. It's not supposed to provide a warm place for ragged bands of industrial

workers to bring their complaints of injustice. The NLRB is located in the

Federal Building, one of those imposing towers. They ran us through metal

detectors at the door, one of the prices of maintaining an empire, then directed

us to a row of swift elevators capable of depositing us high in the Loop sky

in a matter of moments.

I knew

we had problems as soon as we walked in the door at the NLRB. The white secretary

acted spooked when we showed up and went to get her boss. I met our case manager

in the corridor. Obviously middleclass and wearing a charcoal grey suit, around

30, he greeted us, informed us he was the officer of the day, and then attempted

to segregate me from the others by summing me into an office.

I declined

to follow him.

"But

you're the one with the education, right?" he said.

"It's

all of us or none of us," Ken said.

That exchange

irrevocably set the tone of the meeting. We all crowded into a very small

office. The officer of the day sat behind a desk, sweating, facing the rest

of us, all African American or Mexican except me, who had packed into the

room.

"We

don't allow any smoking," he said. Then he just stared at us.

Uncomfortable

with the long ensuing silence, Ken said, "We want to file a complaint."

"Go

ahead." He continued sitting there, sweating, staring impassively at

us.

Ken pulled

out his notes and began recounting the story from the top. He told the officer

of the day about the missing ballot box, the vote fraud, and the complicity

of the union and company. Ken had carefully gone over the dates and times

of days for each event which he methodically ticked off.

The guy

listened with a condescending attitude and occasionally smirked when Ken reached

points in the story when he indicated that he thought items of Federal labor

law had been violated.

At one

point, when Ken said the company had violated the Wagner Act, the kid said,

"Practicing law without a license, are we?"

Ken stopped

reading from his notes and held the guy's attention for a full minute with

a silent eyeball deathgrip. Then he resumed as if nothing had transpired between

the two of them.

Eventually,

I noticed the guy wasn't taking notes. He just sat there impatiently pretending

to listen to Ken while he tapped his fingers on the desk top. Undaunted, Ken

continued to read our story to him to the very end.

When he's

finished after nearly a half hour, the guy simply said, "You've got no

case."

Tom Smith,

an elderly African American man from the South, leaned forward and said, "Y'all

got to be kidding me. What you mean, we don't have no case?"

"I

mean, you've got no case."

Ken Williams

slammed his open palm down on the guy's desk-top. The impact sent papers flying.

Pointing into the guy's face, Ken yelled, "You've got a negative attitude,

man."

The guy

jumped up and stood in the doorway, "Stop this, or I'll call the police."

"What?

You going to call the police on us?" Tom Smith stood up and faced the

guy. He acted utterly astonished. Apparently, based on his conversations with

some of his steelworker friends in South Chicago, he'd put all of his faith

into the NLRB getting things straightened out. I thought of Lexy's warning

to us. I wished we had her legal knowledge to throw into the fight that day.

"You're a fucking honky," old Tom said, giving the kid his best

shot.

The rest

of us starting laughing hysterically. The only other emotional alternative

would've been to jump on the guy and rip him up.

"I

mean it. I'll call the police," the guy yelled into the room.

Nearly

doubled over in laughter, Earl yelled back, "They already done called

the fucking police. We don't care. You think we afraid of the motherfucking

police? We already done seen more police than we ever knowed was around."

Early was laughing so hard he couldn't continue his tirade.

Ken, who

had been seething with anger, finally cracked a smile and started laughing

too. "Come on brothers. We're done here." Ken lead us out. We all

treated the officer of the day to our favorite obscenities as we filed past

him and out the door.

(Ken's final letter:)

"With the 16 of us fired and the rest working under the old crooked contract

we struck over, people ask me, was it all worth it? Even if the strike was

won and we were back at work under a better contract, it is doubtful, unless

we got backpay, that we would have made up the wages lost during the strike.

So what good is a strike? I still think we did the right thing. Before the

strike, company officials laughed at our strike threat saying, 'They'll never

strike. They've never been able to get a strike together before. The Blacks

and the Mexicans can't get together.' That's why they were so arrogant and

obviously crooked. They had the union in their pocket and they thought that

was what it took. Now they know better. We made the company take some heavy

losses, and they are still to this day paying expensive lawyers to use the

technicalities of the law to keep the truth from coming out. The people still

working at Chicago Lard are going to refuse to take a lot of crap. The company

knows it, too. Those who went back are in a much stronger position. The company

knows it, too. The union is going to treat them with respect, now, too. Maybe

we'll get a legal election of steward and do better on the next contract in

order to spare them the embarrassment of another TV crew coming down to Chickenshit

HQ (Ken refers to an action during the strike when they managed to persuade

a TV news person to ask some questions in front of the union's HQ building)

For those of us fired, we have learned some valuable lessons. None of us had

ever been through anything like that before. Now we have. If we gotta do it

again, we'll know better what to do.

"But there is one more reason whey the strike was important to all of us. If no one is willing to draw the line and say we will be pushed no more, then the conditions under which we work will simply get worse and worse. We did what we believed to be right and stoop up to the company, the union, the cops, the rent-a-pigs, the courts, the lawyers, the judges, the fucking U.S.A. government, and Labor Board, the Mafia, and the media. 41 of us stood off all of them for 19 days. We can be proud that we behaved like human beings rather than so many worms. For those who broke the strike by crawling on hands and knees, sniveling all the way back to the company, that's all they'll ever be, sniveling boot lickers and they can be ashamed of that the rest of their days. Remember, my brothers, the workers united, can never be defeated."

Greg Norton

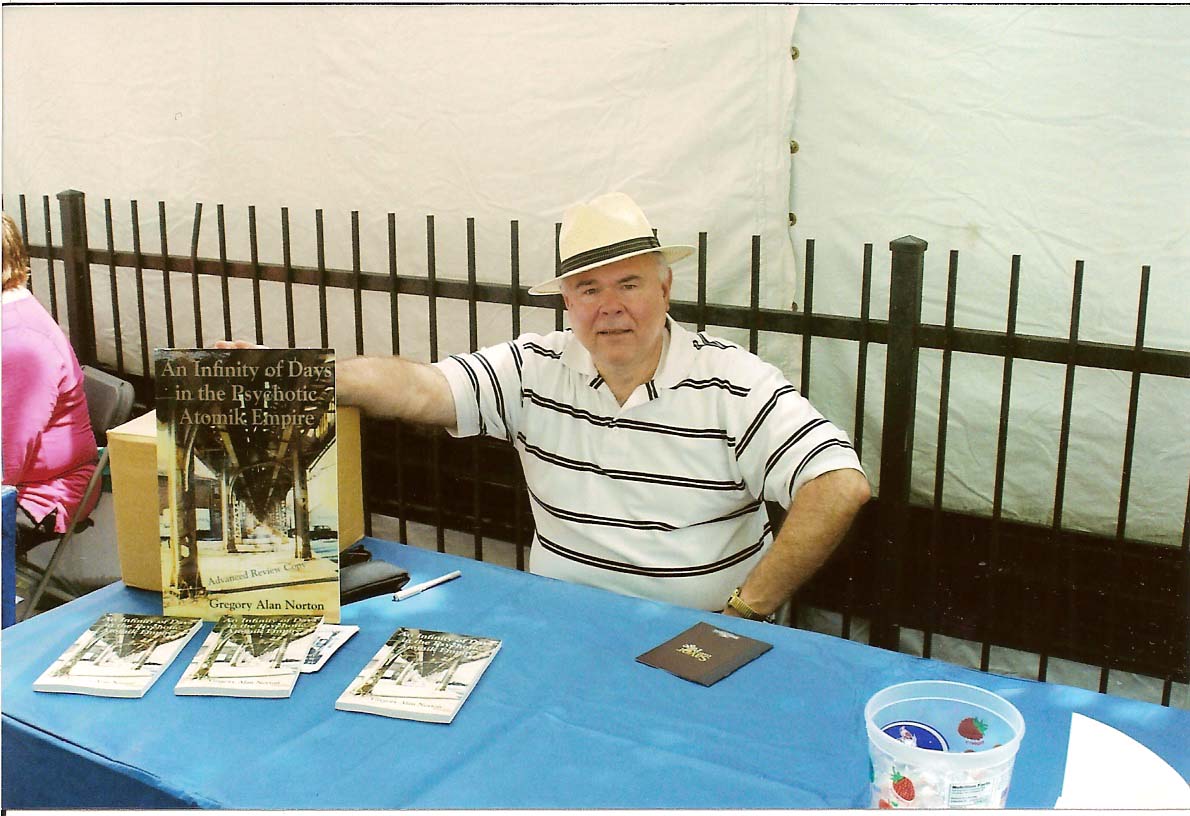

Greg's work can be viewed at his web site, www.gregoryalannorton.com, and may be ordered from him. In addition to his novel, Greg's work includes his short story collection, An Infinity of Days in the Psychotic Atomik Empire, which contains the excellent story, "Factory," published in Struggle not long ago.